Trans-Temporal Visions:

The Film Artworks of Richard Kerr and Kirk Tougas.

I.

“Now, why should the cinema follow the forms of theatre and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts and ideas to arise from the combination of two separate concrete objects?” – Sergei Eisenstein, 1948

The elegant artifacts crafted by Richard Kerr and Kirk Tougas are expressed in a trans-temporal time-tapestry of alluring works that capture moments from our shared celluloid dream-world, one that is decidedly anti-Hollywood and pro-haptic: it also privileges a domain where physical touch is much more important than cerebral reflection. Both artists, who each often specialize in the rarefied realm of found footage, use the actual dream relics recovered in their research to posit an avant-garde take on the bloodstream of visual storytelling. Subversion therefore, and of the most admirable sort, appears to be at least part of their mutual aesthetic agenda.

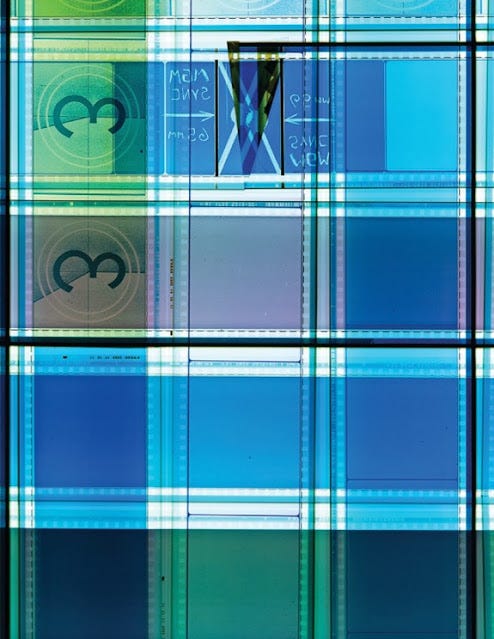

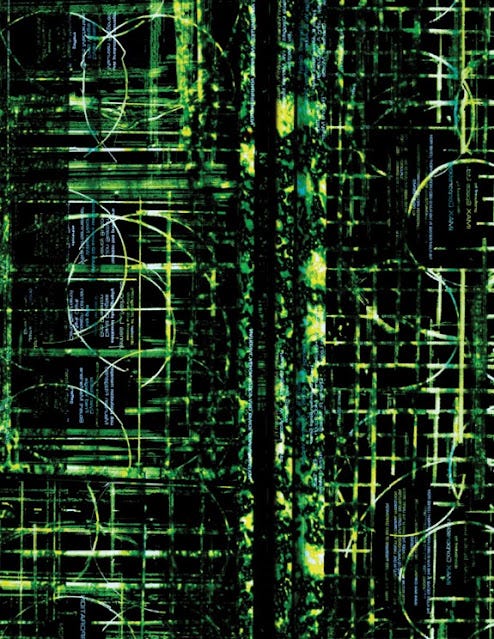

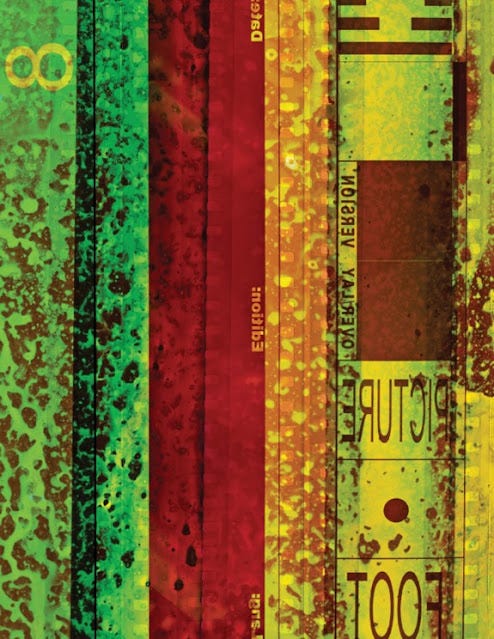

Stillness is embodied in Richard Kerr’s marvelous book project Inventory: Motion Picture Weaving Project, in which he literally weaves portions of actual celluloid film strips within wall-mounted light box pieces that exotically evoke stained glass windows, not from the past, but far into one of several available futures. They also evoke a feeling of semi-precious archaeological relics which could end up in museums devoted to what happened to us. Indeed, they resemble future relics offered by an artist exploring the archaeopsychic domain, probably because that’s exactly what they are: analog cinema linguistics.

The resulting poetics of duration that Kerr achieves is subtle yet profound, since by using actual found film stock, leaders, and studio countdowns, he meditates on the optical language of film itself, and on its syntax, so to speak. This is the domain of the mediated montage of individual shots and frames, of both moving and still lumière paintings which cause us to pause, ponder and register the deep intuition of the instant once stilled.

MGM Sync, 2008

Kerr’s use of found footage in his lightbox compositions is, in other words, a construction of sentences and paragraphs out of the basic system and syntagm relationship between images and oneiric ideas. In Inventory, he illustrates how an innate penchant for storytelling can evolve over the years as it undergoes significant aesthetic and technological development and becomes ever more subtle in both form and content.

Godard Space Flight, 2021

As to the question of whether Kerr’s source materials have become more and more rare as the digital domain colonizes our world, there might indeed be an element of what for me feels something like an elegy to his methods and his works. This is at the beating heart of Kerr’s marvelously compulsive enterprise: to plumb the depths of the mind under the influence of a drug called cinema, one where the only antidote is more cinema.

Technicolour Countdown, detail, 2022

*******************************

II.

“The assertion for an art released from images, not simply from old representation but from the new tension between naked presence and the writing of history on things; released at the same time from the tension between the operations of art and social forms of resemblance and recognition. An art entirely separate from the social commerce of imagery.” Jacques Ranciere, Future of the Image (2003).

Kirk Tougas takes a drastically different narrative approach to subverting the storytelling modes of commercial filmmaking: in those projects of his that utilize found footage he repurposes the story strips by splicing and dicing the actual fabula, or tale, of the original and employing multi-durational repetition strategies which render utterly surreal some of source-origin’s intentions. He draws our attention to what I often call the cinematic uncanny: the act of seeing, of watching in a dramatic manner which renders our quotidian awareness utterly voyeuristic.

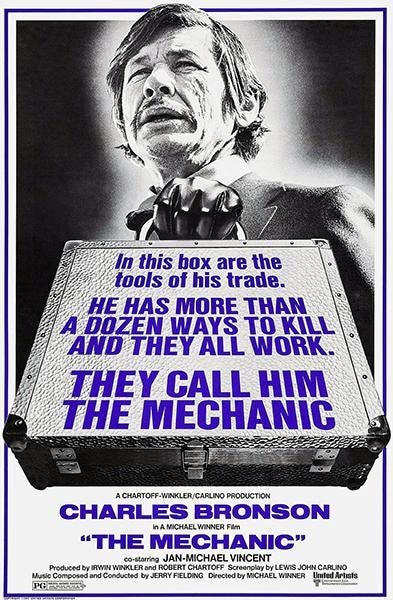

Case in point, his almost fetishistic engagement with what amounted to a 1972 b-action movie starring Charles Bronson, in which he elevates the macho ethos into a veritable commentary on the how and why of Hollywood’s seductive selling of alternative realities masquerading as our own manipulates our emotions. Context is everything. And re-contextualizing an action icon by recycling his looming profile for a small eternity tends to invigorate some rarely visited neighbourhood in our collective unconscious, that subterranean place the archetypes go to be homeless. Kirk Tougas goes even further: he implores the viewer to actively engage in watching their own watching.

The Politics of Perception, Kirk Tougas 1973

Both these film artists utilize found footage, however the former memorializes the actual celluloid in sculptures while the latter permits us to continue watching the celluloid through projection while mutating the image beyond recognition. The use of either found or appropriated footage and its dialectical transformation into a new motif/meaning is an aesthetic tradition which has been in the ascent ever since modernists first began experimenting with that most modernist of mediums, the cinema. But few have approached and analyzed the image archive itself with the aplomb and clarity of Tougas across a diverse range of pieces and most emphatically in his recently remastered and restored two-part 1973 film Letters from Vancouver.

Letters from Vancouver consists of two distinct portions which can be viewed separately or in sequence: The Politics of Perception (1973, 16 mm, 33 minutes) and The Framing of Perception (1973, 16mm, 33 minutes). Both of them are exemplary indications of how far afield from ‘entertainment’ a visual artist can travel while still maintaining a mesmerizing hold on the viewer as he continually asks highly pertinent questions about what, or who, forms our consumption assumptions. His is a prime example of non-verbal cinema at its finest and most psychologically incisive. As such, he concentrates on what I would identify as the optical language of cinema embedded in time.

In Part One of Letters From Vancouver, The Politics of Perception, Tougas takes us deep into the realm of persuasion and mood manipulation, a domain of images otherwise known as promotion. The product being sold is, of course, our own perception, and subsequently all of our conceptions about it. By working and re-working a piece of art over the course of nearly fifty years, I believe he is also engaging in the production of a trans-temporal production, one which is not only nourished by duration in its original fabrication but also replenished by Gaston Bachelard’s crucial notion of durée as a dialectical process lodged in reverie.

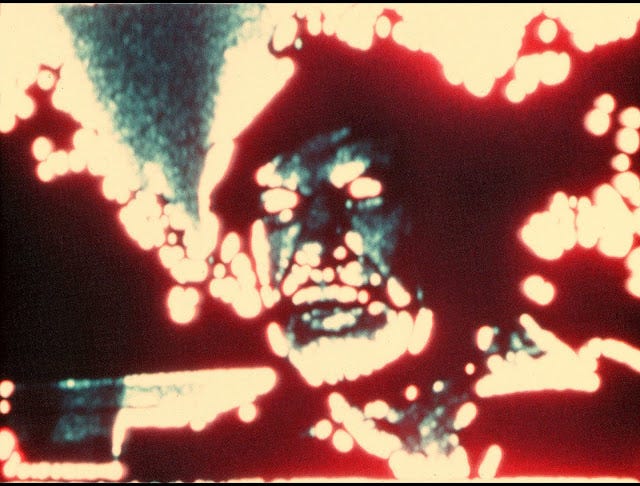

When Tougas, for instance, recycled into perpetuity the promo trailer for a Charles Bronson thriller film The Mechanic (1972), for Part One of Letters from Vancouver, The Politics of Perception, while also engaging in a precise surgical decay and entropic declamation of its ‘message’, all the way into optical oblivion, he is exercising precisely a kind of heightened attention to his own optical language. A question appears on screen: “How do you consume?,” followed by a secondary title: “An experience.” The concept is deceptively simple (repetition some thirty-three times of a B-movie promo trailer for The Mechanic) yet this basic clichéd communication we are all so familiar with only begins to assume its full impact as it builds into an avalanche of super-saturated colors rendered utterly abstract in content, except for the promo soundtrack.

It is, however, in the second segment, The Framing of Perception, that collage is employed to a higher degree than the montage tools of what I can call his ‘Bronson epic retelling’. For instance, a multiplicity of sources is employed, as opposed to a meditation on a single message being allowed to atrophy before our eyes, and this waterfall of images, some political, some commercial, all aesthetic, some even anaesthetic, achieves a splendid kind of apotheosis or crescendo.

A frame from the popular television series The Avengers

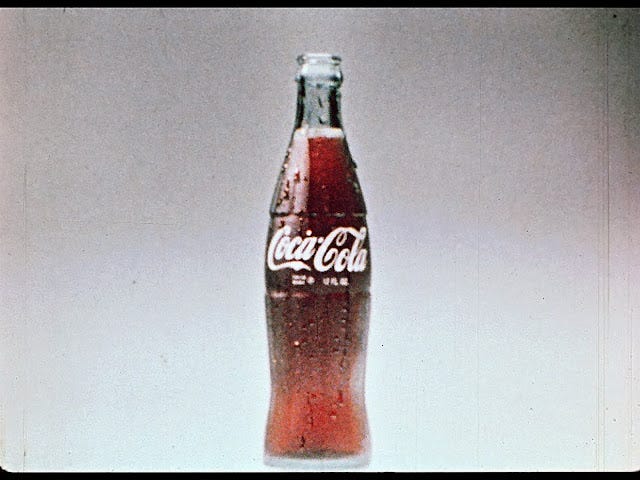

The ultimate object of desire, presented in a monumental moment.

That growing tidal wave of images is the chief signifying element within which Tougas asks us to question the nature of our addiction to images per se and our fetishistic appetite for the objects and services which they so often designate or signify. Once again, we are brought face to face to face, with the Janus-like nature of media consumption, until, if we are persistent enough, we become suddenly aware that our own mediated consciousness is the actual product we are being ‘sold’.

And it is here, after being faced with an old analog video camera aimed at us, that that the true content of The Framing of Perception begins anew, in a manner not unlike the repeated and recycled trailer for The Mechanic, but this time more in keeping with Brion Gysin’s infamous “dream machine,” a device which allowed the user to enter into a technically induced trance state through the repeated flicker of a circular disc rotating through cylindrical background vessel. This alarming incursion occurs at roughly the halfway mark, or fifteen minutes into the framing saga, and is eventually reversed by the flickering spotlight, almost strobe-like in its intensity, with a black disc in the throbbing center surrounded by an ever-accelerating white border.

Both Kerr and Tougas emphasize visually what Alfred Hitchcock once opined, that cinema is all about the empty white rectangle: “I have no interest in pictures that I call photographs of people talking. I have that empty white rectangle to fill with a succession of images, one following the other. That is really what makes a film.” Indeed, provocative and innovative cinema artists such as Richard Kerr and Kirk Tougas, it seems to me, actually want us to look through their films even more than at them. We need to read them as we would a found literary text or an archival object. Employing found footage in this manner can render it as a kind of Rosetta stone that must be deciphered in order for us to arrive at meaning. We ourselves are the elusive story which we, in the end, are all trying to comprehend.

Thanks, Donald,

You always have thought provoking ideas that create more ideas and questions and you quite Bachelard which makes a fine way to approach Art with a capital A. I just watched Rose Hobart to go back to the 1930’s for a bit of early context.