“Dying is easy, it’s comedy that’s hard.”

Comedian George Burns, reputedly on his deathbed.

“Comedy aims at representing men as worse, tragedy as better than they are in actual life.”

Aristotle, Poetics.

The stern inventor of comedy, most infamous for laughing at Socrates.

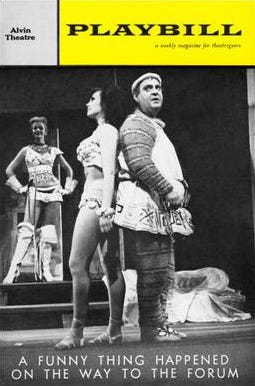

I’m reminded of a certain Stephen Sondheim song from his 1962 musical called A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, which was partly inspired by the farces of the Roman playwright Plautus (254 – 184 BCE). Specifically it was about a certain character named Pseudolus, who daily demonstrated the dilemmas of the dual nature of our existence. That song, Comedy Tonight, embodied our urge to put off tragedy until tomorrow, in order to enjoy ourselves with a good comedy today, as we remain torn between two lovers: tears and laughter. “Something appealing, Something appalling, Something for everyone: A comedy tonight! No royal curse, no Trojan horse, And a happy ending, of course. Goodness and badness, Panic is madness. This time it all turns out all right! Tragedy tomorrow, Comedy tonight!”

Two and a half millennia after the brilliant ancient Greek masters who invented comedy, figures such as Aristophanes, Hermippus, Eupolis and Menander, we’re still in dire need of their instructive medicine. These days however, as exemplified by our modernist masters during the golden age of Hollywood, both in the screwball and manners modes, figures such as Lubitsch, Leisen, Sturges, Hawks, Brackett and Wilder, we’re still learning to laugh at ourselves and our follies as a means of hopefully restoring our optimism by disposing of our own frequently ominous seriousness. Life is short, says comedy, give yourself a break.

At first glance, that seemingly off the cuff and probably tipsy remark made by Dorothy Parker during one of the Round Table discussions holding forth at the Algonquin Room in New York may have felt like one of her frequently brisk bon mots. “Comedy is tragedy plus time.” But upon closer examination, it just might reveal a deep insight into not just the human condition, but also the theatrical devices we use to embody its paradox in entertainment. The notion that comedy might really only be tragedy viewed from another perspective, that of longevity and experience, also brings to the fore even more perplexing questions about what makes us either laugh or cry together in theatres devoted to watching either live enactments or filmed depictions of human behaviour. As an editorial note, Dorothy may have been repeating a similar remark made by Mark Twain, and after her it may also have been borrowed by Carol Burnett, among others.

The Round Table debates and discussions, those caustic, sardonic, alcohol-fueled satires occurring in real time by a privileged coterie of mutually admiring and competitive writers, who themselves described it as a “ten year long lunch” (lasting from 1919-1929) have entered a kind of legendary realm of writers, authors and journalists who indulged themselves in unbridled self-ridicule as well as the lampooning of their peers and fellow wordsmiths. And as New York historian Barbara Maranzani so deftly demonstrated for the Biography newsletter, along the way they became symbols for the Roaring Twenties in a hip precursor to the Swinging Sixties. They did so by becoming the epitome of the glamour and excitement of a heady decade, cool trendsetters dining on witty banter and becoming household names by establishing an unintentional cultural legend.

Dorothy Parker, American humourist extraordinaire, 1948, (NY Times)

But even their very first meeting was inaugurated mostly as a joke on one of their revered circle, Alexander Woolcott, whose endless stories about his war exploits overseas began to grate on them, so they invited a group of their fellow critics and writers to an afternoon party at the Algonquin Hotel, near New York’s theatre district, to conduct a sort of kindhearted roast of their mutual friend, possibly the first of its kind. Woolcott was apparently as delighted by receiving their witty attention as they were delivering it, and the group decided to meet the very next day for lunch, at a long table in the Pergola Room, after which the hotel manager decided to give them a more semi-private setting at the Rose’s Room’s round table, thus launching a ten year long habit. Regulars included Woolcott, satirist Robert Benchley, Heywood Broun, Robert Sherwood, playwright George S. Kaufman, Noel Coward, filmmaker Herman Mankiewicz, editor Harold Ross, Edna Ferber, Dorothy Parker, and a steady stream of interlopers or invited guests, if they were cool and sharp enough to survive.

“As the group grew closer, they began spending nearly all their time together” Maranzani observed. After lunch they would frequently retire to the apartment of illustrator Nyesa McMein for cocktails. They accompanied each other to dinner and the shows they would later review, followed by illicit drinks at Prohibition era speakeasies. Their exploits and witticisms were frequently reported on by a popular syndicated column, The Conning Tower, and the publicity made the Round Table members stars, with tourists and New Yorkers alike gathering to look in at their daily lunches.” No doubt that audience encouraged the group, then known affectionately as “the vicious circle” or “the poison squad” to speed up and amplify their repartee even more. Ironically, there was also a late night poker-club, nicknamed The Thanatopis Literary and Inside Straight Club, a Greek term for the contemplation of death, meeting nightly upstairs at the Algonquin.

Charlie Brackett slumming at the Academy Awards ceremony, 1950

When Charles Brackett returned from his expatriate stint in Europe after the war, where he was already participating in like-minded gatherings of indulgent visionaries in Paris with Yankee literary superstars, his friend Harold Ross not only invited him along to the Round Table clique but also invited him to be the first drama critic for a new little magazine he launched in 1925, The New Yorker. While I’m not positive that Brackett was present on the same day that Parker made her famous quip, I am certain that she repeated it so often subsequently that he was sure to have overheard it in one incarnation or another. I’m equally certain that it sank in, lodged in some deep private place inside him which would rise to surface of his unconscious ten years later, when like his friends Benchley, Ferber and Parker, he was seduced by Hollywood to decamp and set up shop there as a writer for hire.

Maybe it was the proximity of their Thanatos-inspired poker club, with its curious Greek-tinged identity, or maybe the depth of Parker’s quip situating tears and laughter so close together, or maybe it was the audacious spectacle aspect of their Round Table luncheon ‘discussions’, with any old passersby welcome to gawk at and relish their swift repartee as if they were in a public amphitheatre in Greece itself, where comedy first came into being, but all these things together fueled my interest in putting comedy itself on the operating table for an examination. For the purposes of an in depth dissection, a kind of autopsy of laughter and what provokes it, I turned to an important book from 1965 which I recall being a revealing exploration of this quirky subject. Comedy: Meaning and Form, by Robert Corrigan, has long fascinated me for the way it so effectively showed us how comedy and laughter are serious business. Indeed, the comedian Steve Martin titled one of his early albums Comedy Isn’t Pretty, and the great comic actor George Burns is said to have left a revealing deathbed remark about comedy being more difficult than dying, as his last words.

In Corrigan’s book he takes us on a guided tour of an ancient craft, first materializing in Greece’s golden age, in search of answers to the basic question: what’s so funny? And by peering into the origins of the invention of comedy, reputed to have been brought into being by the playwright Aristophanes, who lived between circa 446 bce in Athens and 386 bce Delphi. He would be among the first creative thinkers to intentionally make fun of an otherwise serious historical figure, Socrates, in a manner that seems to have single-handedly prefigured both the satire and parody that came to be recognized almost two millennia later in the screwball comedies of Hollywood.

Corrigan sums it up quite nicely: “Strangely enough, while comedy’s intriguing complexities have always been of special interest to philosophers, and more recently psychologists, they seldom have been dealt with in a systematic way by critics or theorists. But this state if affairs seems to be changing. In a time when our next tomorrow must always be in question, comedy’s tenacious greed for life, its instinct for self-preservation and its attempts to mediate the pressures of our daily grind seem to qualify it as the most appropriate mode for the drama of the 20th Century.” But despite this near interest in something which previously had not been taken seriously, the author also cautioned against pitfalls that might cause one to miss the point all together. “To deal with tragedy” he observed, “is relatively simple. Comedy, not so much.”

There was an important lesson in the first recorded attempt to take comedy seriously, one that evolved continually from the classical age right up to the satirical Algonquin Room Round Table discussions. Once again, and perhaps surprisingly, we are reminded of the prophecy of Plato’s Symposium, at which after an evening, night and early morning of discourses, Socrates is still rambling on. He at long last starts to discuss the nature of comedy, and he observes cannily and proposes his own theory that surely comedy and tragedy must both arise from the same foundation. “To this,” Plato clarifies, “they were constrained to assent, being drowsy, and not quite following the argument. And, first of all Aristophanes, dropped off to sleep.” “Such was the charm,” Henry Myers has explained, “of the first theory of comedy. We leave the Symposium with the unforgettable picture of an eminent philosopher putting an eminent comic to sleep with a lecture on the comic spirit.”

Later, we would all be edified further by Aristophanes as the father of comedy, and whether or not he was actually sleeping or merely pretending to be sleeping, when he used his fearful powers of ridicule to lampoon Socrates, and indeed, any other ponderous philosopher speculating idly on life’s deeper purpose. Indeed, Plato himself singled out the Aristophanes play The Clouds, 423 bce (origin of the mocking term cloud-cuckoo-land) as a form of personal slander, one that contributed in part to the trial and subsequent condemning to death of Socrates. Thus, laughter is really no laughing matter at all. And up to this point in classical cultural history, a so-called comedy was officially defined solely as “a tragedy with a happy ending”, up until Aristophanes that is, the Steve Martin of the ancient age, claimed for it a front stage position as an independent art form all on its own, from the beginning of a play to its conclusion.

“The constant in comedy”, Corrigan observed, “is the comic view of life, or the comic spirit: the sense that no matter of how many times a man is knocked down he still manages to pull himself up and keep on going. Thus, while tragedy is a celebration of man’s capacity to aspire and suffer. Comedy celebrates his capacity to endure.” Perhaps no other writer, apart from Samuel Beckett in the last century, managed to make of the intimate connections between the tragic and comic a marriage which was the beating heart of almost everything he ever wrote, especially his Murphy, Molloy, and Godot. The critic and theatre theorist Eric Bentley identified an important urge here in his Life of the Drama: “In tragedy, but by no means comedy….the self-preservation instinct is overruled. The comic sense tries to cope with the daily, hourly, inescapable difficulty of being. For if everyday life has an undercurrent in tragedy, the main current is the material for comedy.”

Christopher Fry also commented, in one of the essays compiled in Corrigan’s book, on how the two currents flow together to form the mainstream of life: “Laughter did not come by chance, but how or why it came is beyond comprehension. The human animals, beginning to feel his spiritual inches, broke onto an unfamiliar tension in life, where laughter became inevitable. But how? The difference between comedy and tragedy is the difference between experience and intuition.” After the twentieth century, an era when most universally accepted systems and hierarchies ceased to be viable, all human experience seemed to become either equally serious or equally ludicrous, or even both at once. As that great playwright of the absurd, Eugene Ionesco maintained, “It all comes down to the same thing anyway: comic and tragic are merely two aspects of the same situation, and I have now reached the stage where I find it hard to distinguish one from the other.”

The comic gesture, what Pirandello called the comic grimace, makes use of the very ludicrousness of comedy to show that life itself is absurd, and Corrigan reminds us that “The lines of the comic mask have become those of the tragic mask: in them we find that the relationship of means to ends is a paradox. Whereas in the comedy of earlier times, comic means were used to comic ends, in the modern, comic means are employed to serious ends. The comic has become a transparency through which we see the serious. Comedy is unquestionably the proper mirror of our times; but it is also true that it reveals our life to us: as through a glass darkly.” Although comedy in various forms has existed, if not since time immemorial then at least until Aristophanes started snoring during a Socrates dissertation, it was in the 20th Century that it rose to an imperial kind of prominence formerly only accorded to drama and tragedy.

This may, of course have been due to the fact that the 20th Century was one of the saddest and most woe-begotten periods in human history since the Medieval era, or it may also have been since the industrial age saw the transmission of images and stories provoking laughter reach a peak level of mass distribution. And Hollywood was naturally the epicenter of that huge pop culture wave, just as its designers intended that it should be. So, the invention of the comedic art was one thing, but the perfecting of its codes was yet another. One of the finest explorations of the unique parameters of modern and contemporary comedy was penned by Steve Vineberg, in his High Comedy in American Movies: Class and Humour from the 1920’s to the Present. “High comedy, also known as comedy of manners, was invented by the British Restoration playwrights in the late seventeenth century. Conventionally, high comedy is elevated in both style and subject matter, and class is a felicitously inescapable boundary. When most people hear the term ‘high comedy’ they think of The Importance of Being Earnest, or the plays of Noel Coward. But we Americans have our own high comic playwrights, whose period of popularity came between the two world wars. And what makes American comedy of manners so fascinating is the ways in which American identity—historically in tension with the distinctly undemocratic substance of the high-comic universe, interacts with that universe to produce a series of variations on the genre.”

Rowman and Littlefield Publishing

In Vineberg’s fine study, the reader is taken on a guided tour of the comedic traditions as uniquely exemplified by the Yankee sensibility. “High comedy is one of several comic genres known to American audiences; the others are romantic comedy, burlesque, hardboiled comedy, sentimental comedy, parody, black comedy, satire and farce.” Clearly what Corrigan called the comic spirit, and its national muse, is almost as varied as the complexities of American character itself. Vineberg also further reminded us that “High comedy is a very delicately crafted thing—a soufflé. In order to work best it must be as light as gossamer and seem easy and slight and entirely superficial; that’s how writers and director’s produced what, in Pauline Kael’s view, Lubitch produced; ‘almost perfectly preserved iridescent make believe worlds’. What the finest high comedies accomplish is to seem superficial while actually being profound.”

The immediate experience of popular culture is precisely the one we need to embrace to fully appreciate the anarchic elements inherent to great comedy. Karnick and Jenkins further elaborate however, that “Comedy’s dependence upon stereotypical characters and situations would be one example of the way that redundancy gets built into the systems of genres. Yet at the same time, the absence of novelty would make the repeated consumption of genre films a pleasureless activity. If genres provide the framework of shared assumptions which make a popular film understandable, genre also defines the space for potential innovation and invention.” The same authors also emphasize that despite their adherence to, if not conformity, then classical norms, romance based satires and parodies still off us an ample space for excess, virtuosity and spectacle. Jenkins observes accurately that the built in absurdity of impersonation mimics acting itself, to begin with, but also presents a perfect opportunity to showcase linguistic highwire skills. “The bantering dialogue and rapid delivery which characterizes screwball comedy has been linked to the film’s overall conception of male-female relationships. These aspects of performance style, as Tina Lent notes, fit comfortably within an ideology which sees men and women as potential playmates as well as lovers. The smooth interaction between two performers can suggest how much these characters belong together.”

Such a nimble insight in body language further reveals what the critic Pauline Kael described as “That sustained feat of careless magic we call thirties comedy.” Even more importantly, and as also stressed by Tina Lent, “Screwball comedy redefined film comedy of the 1930s and the conventions of this new genre were the third major source for the modification of the portrayal of gender relations on the Hollywood screen. Not only was there an equal teaming of a male and female star in screwball comedy, but for the first time the romantic leads were also the comic leads. The romantic leads often had eccentric qualities, and their unconventional behaviour was both a form of social criticism and anarchic individualism.” As James Harvey astutely declared in his wonderful study Romantic Comedy in Hollywood: From Lubitsch to Sturges, one salient fact remains for all of us to savor: “Comedy” Harvey asserted, “was Hollywood’s own essential genius.” Even if it was originally invented in classical Greece over two thousand years ago as a means of skewering pompous philosophers or politicians, few things are quite as effective as laughter when you need a weapon to disarm your opponent.

Thanks Larry, I've always been fascinated by the origins of comedy...or even of laughing in general. In fact, I suspect there are unusual parallels between the darkest film noir and the lightest screwball comedies. Underneath I think they're somehow identical.

Thanks Donald. You have laid it out beautifully and make me want to read more as well as laugh more!