(This article first appeared in Critics At Large)

“Someday, everything is gonna be smooth like a rhapsody, when I paint my masterpiece…”

Robert Zimmerman, AKA Bob Dylan

Dylan joyfully posing for his 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature (CNN)

In my 2008 book entitled Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer Songwriter, I had a chapter on the erstwhile Mr. Dylan, who apart from various minor differing personal tastes most astute people can now readily agree is one of the pre-eminent literary and musical artists of our era, of several eras in fact. His chapter opened my book for obvious reasons: he has single-handedly etched the template for what a singer-songwriter in the contemporary age is capable of achieving, assuming that songwriter lives long enough to become an elder statesman of his or her ancient craft, as Dylan has clearly done. The chapter on him was called The Storyteller: To Be On Your Own, and it encapsulated for me, without my even realizing it almost fifteen years ago, what made him not just a folk/ pop/rock star but both a Nobel-worthy novelist and an island unto himself.

I didn’t quite have the nerve to actually make this outlandish claim in my book at that time, and my editor probably would have talked me out of it with the obvious disclaimers, something along the lines of “Oh come on Donald, it’s not like he’s Herman Melville or John Steinbeck or something, the guy makes popular records of songs.” True enough, he’s popular, though for some of us his fame and celebrity might belie what his true and proper role really amongst us is. He is, of course, precisely the same kind of dark mirror that both Melville and Steinbeck were, and in some ways he also shares some of the shimmering gifts of a John Cheever or John Updike, while we’re at it, whose short stories likewise contained those crystallized essential ingredients exploring what it means to be both an American and a human being at the same time.

Steinbeck contemplates his surprising future

In a couple of months Dylan will be 82 years of age (the same age as Neil Diamond, who has just finally retired from the concert stage) but he’s still out on the road and probably will die one night in the middle of a concert singing some new and hard to recognize version of one of his classics. The John Cheever story that easily could have been a Dylan song was called The Swimmer, and the Melville story that could have been one was called Bartleby, The Scrivener. Both have the same sense of foreboding doom and weird irony that Dylan work has utilized with as much sarcasm as another grizzled and difficult to fathom American poet, this one from Idaho of all places, Ezra Pound. It was the dangerously dotty but seriously gifted Pound who stated that “Literature is news that stays news.” By which he meant, I think, that both Homer and Shakespeare, James Joyce and himself, were all equally pertinent to today’s world, and were content-providers merely using different delivery-systems. To these names on a stellar list of literary titans I could also add both the late lamented David Foster Wallace and the still very much with us Bob Dylan.

Well, now Dylan has won the Nobel Prize for Literature and is indeed in the same hallowed if surprising company as Hemingway and Steinbeck, and I almost feel like contacting my American editor of Dark Mirror and exclaiming, “See, I told you so, I told you I wasn’t crazy.” But, as one of my favourite fictional characters in American literature, Melville’s Bartleby, often declared, in answer to almost every question ever put to him, “I’d prefer not to.” Indeed, this short phrase may well be what I’d call the creative code by which Dylan conducts his poetic affairs in the world. Could you explain this song to us Mr. Dylan? Could you help us understand why you received the Nobel Prize Mr. Dylan? Could you clarify the meaning of some of the obscure metaphors in ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’, Mr. Dylan?” He’d prefer not to. And after all, why should he? What they mean is our problem, not his.

Poet-mystic, maniacal-minstrel, troubled-troubadour, surrealist-folk artist, chameleon-rock star, existential-entertainer, creative genius. Each of these terms well applies to the musical mystery that is Bob Dylan. A couple of terms you will not read in this essay however are “voice of his generation” or “protest singer”, partly because he so deplores them being misused for him that they can no longer be trusted, but even moreso because he was and still is a critical voice for multiple generations and a singer-songwriter-musician who needs to more properly be positioned closer to protesting Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, WH Auden and TS Eliot. He won’t like that either, but as one of his paler imitators once crooned “It’s all right now. I’ve learned my lesson well. You see, you can’t please everyone so I guess you have to please yourself.” He has made pleasing himself into an art form all by itself, and by doing so he has been pleasing us for nearly 60 years as the genuine voice of our own discontinuous discomforts, our disjunctive demands, our delusions, and our delights.

And what an inter-generational voice it is! It still growls and croaks a unique sonic message after all this time at the garden party. And strangely enough, the sentiment is shared between Ricky Nelson’s Dylanesque take on the music industry and Dylan’s own take on how smooth his own rhapsody will be once he paints his masterpiece, which is something he did long ago. We can even all take our pick of which painted song qualifies for such a status simply because he’s crafted so many, in so many different styles, over decades at his lofty easel. Just as Fleetwood Mac were only a traditional blues band for about 5% of their long career, so too has Dylan only been a traditional folk singer for about 5% of his own staggering saga, though unlike those former musical chameleons he has given himself the freedom to travel back and forth from his historical roots in the past and into his intellectual roots in the future. In fact, he is partially responsible for the musical future we all now live in, and his sung novels are documentary evidence of what being sentient in the 20th century, and a large chunk of this one, really means. I thus maintain that he is our John Steinbeck in sunglasses.

One of the ways he has manufactured this unique creative freedom he displays, an elevated format that seemingly only he could have managed to accomplish, was to invent a new kind of anti-folk music that includes any and every style he puts his mind and hand to, thus achieving a liberty that more inhibited artists can only dream about. But as his book of lyrics suggests, he is also, in my humble opinion, not only a storyteller but an actual novelist, since I believe every song to be a single chapter in a very complexly layered novel. Or perhaps it’s every recorded album that is a chapter in a meta-novel. Something along the lines of either Ulysses or Finnegans Wake. To that extent he is the very embodiment of what a classic minstrel is and does by definition: a bard who performs songs whose lyrics told stories of distant places or of existing or imaginary historical events, one who often creates their own tales but just as often memorializes and embellishes the work of others. No one ever deigned to ask Ezra Pound what he meant, and if they did they got the same sarcastic grumbling as Mr. Zimmerman always dispensed so artfully.

In Larry Smith’s 1999 study of Pete Townshend, he astutely identified this as the “minstrel’s dilemma” and charted its course in that special case. But unlike the mercurial and uneven Who-founder, Mr. Dylan has clearly solved that dilemma, though solving it is slightly different from resolving it, as we shall see in our brief sojourn sailing on his astonishingly gifted river. The original meaning of the word dilemma, from the Greek, of course, just like almost everything else is, meant proposition, and it reveals much in this case: a problem offering two possibilities, neither of which is practically acceptable. One in this position has traditionally been described as being on “the horns of a dilemma” with neither horn being comfortable. It is therefore a double proposition, and especially so in the case of Dylan, clearly a self-defining monument to paradox itself, who has so often explored ethical dilemmas, frequently in the subjects of love and honor, where the choice between two imperatives leads to more confusion rather than to more clarity.

In the interests of at least making an attempt to search for some clarity in all things Dylan therefore, this brief essay’s first proposition, or is it the fourth, is to acknowledge that this artist is a complicated and heavily overgrown landscape which often defies easy or effortless exploration. The songs themselves are the best way to explore him, but not always the most satisfying way to understand him. And of course, the same could be said of Shakespeare or Cervantes, someone who captured the essence of their shared time as deeply as Dylan may have captured the quintessence of his own.

Dylan’s work is a complex terrain, one that’s also exhaustingly long, but certain landscapes are so overgrown with myth that they’re best explored from the air. An aerial view provides the best way to access his geological contour lines if you will, since his life and work landscape is so drastically different in its evolutionary features that to stand in one little field or pasture of its opulence, as lovely as any one field may be, is to lose the connections and continuums between that field and the one before it, and with the one after it. So I’m proposing something of a helicopter flight over his domains, one where the vehicle first brings us up high enough to see the whole of a dauntingly big picture, and then regularly swoops down low to get a closer view of the foliage, the trees, the rocks, the fences themselves. The sung chapters in his novels, so to speak. But this helicopter never lands.

He has also always been rhapsodizing, since a rhapsody (again from the Greeks) is a work of epic poetry, or part of one, that is most suitable for recitation all at one time, hence the aerial view of something just too big to traverse in little side walking trips. He would hate this too probably, but his best exemplar would be a John Milton, or even the very first tale ever written down (by the amazing Sumerians) the epic of Gilgamesh that contains the original myth of The Flood. Thus a rhapsode is a classical professional performer of epic poetry, and a rhapsode is what he is, whether he likes it or not: all his songs can be merged naturally into one long ode, each individual song being a single verse in that epic ode. The origin of the word rhapsode means, after all, “to sew songs together”. Suddenly the sense of irony in his title for a an early career live album takes on even more weight in light of Gilgamesh as well: Before the Flood, 1974, with his remarkably suitable Band, and with whom he would also record his true Gone With the Wind: The Basement Tapes, in 1975.

So during this brief fly over, we can envision the depths, and the heights, of his artistic philosophies, his creative vision(s), his stylistic tendencies, and his contributions to the classical craft of bardhood. He is and will be, I readily assert, a kind of cuneiform tablet that future participants in our sad and glorious civilization will unearth either accidentally or intentionally, when they try to piece together the complex beauties and horrors of being a human dweller on the earth in the 20th Century. In that last respect, I’d also compare what I’m calling his novelistic odes with those novels of a fellow American author who also won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Sinclair Lewis, the very first American to do so in fact, in 1930. Lewis’ incisive glimpses into what it means to be an American in the 20th Century, from Main Street in 1920, to Babbitt in 1922 and Arrowsmith in 1925, were somewhat shocking revelations of the underbelly of Yankee pretensions at the time. Nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for Arrowsmith, he refused to accept the honour, saying that the Prize was meant to go to a novel that celebrated the wholesomeness of American life, something his own books did not do. After the achievement of the harrowing It Can’t Happen Here, a novel which now seems like a documentary of precisely what now is happening here, he relented and was awarded the Nobel Prize however, something which Dylan also had no trouble accepting either, despite his notoriously reticent nature.

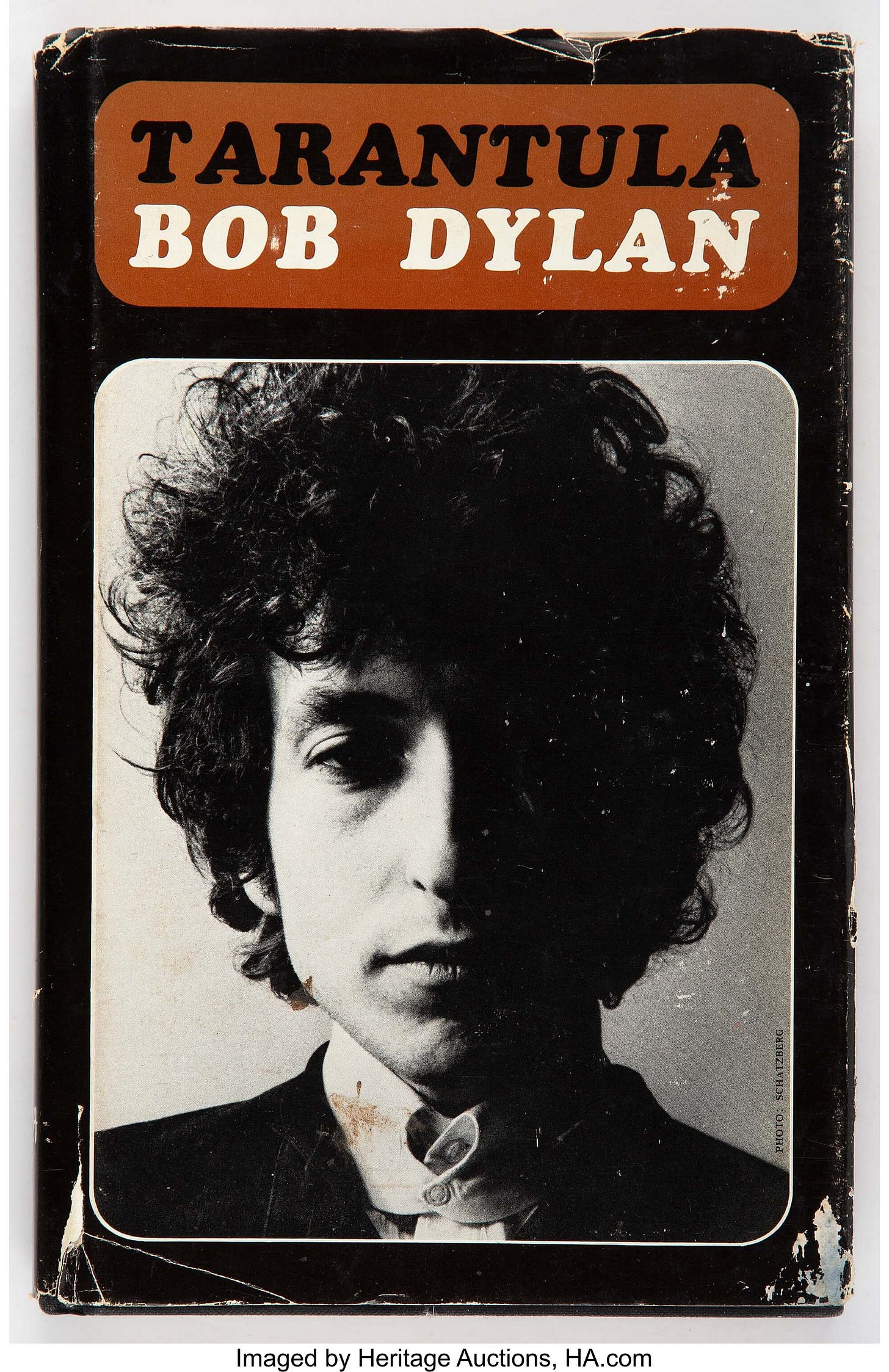

The other day I had one of those prophetic dreams that feel utterly lucid, what the Tibetan Buddhists call a clear light dream, in which I met Dylan as he was back in perhaps about 1966, the year he released Tarantula, one of the scariest collections of prose poems since Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, or maybe Burroughs’ Naked Lunch. For some reason known possibly only to Jungian analysts, in the dream we were painting the walls of a legal office together and trying not to get any splatters on the pretty mahogany desks, as he was doing the walls and I was doing the trim. I pulled out my old copy of Tarantula, called back then a fragmentary novel (as good a way any I suppose to describe the indescribable) presumably so he could sign it, but instead he just painted right over it. It had a broken spine and missing middle pages, and he asked me why it seemed so damaged, to which I responded, “For the same reason that you do, I was reading it the same way you wrote it….under the influence of supernatural forces. I guess my eyes must have torn up the words.” He just smiled and said ‘good luck’. True story, a real dream. Only in our dreams I suppose. But as another important poet, Delmore Schwartz, another of those who strongly influenced Dylan himself once so succinctly put, “In dreams begin responsibilities…” As usual Delmore Schwartz got it right.

If we remember that Dylan is a rhapsode, and he’s only singing one long epic song in the end, it might make the rough journey just a little more smooth as he paints his masterpiece, which he’s now done several times over. It is, of course, a self-portrait. Maria Popova once characterized his ongoing self-portrait very well when she described Dylan’s “singular creative footprint” in her assessment of Paul Zollo’s fine 1991 interview with the singer-songwriter in his excellent study of the genre, Songwriters on Songwriting. Muriel Rukeyser has an equally spot on definition of his poetics as an art that relies on the “moving relation between individual consciousness and the world.”

Without pushing my analogies or metaphors too far, but also without much mental effort at all, I find it easy to detect a deep subterranean link between Steinbeck’s novels such as Tortilla Flat (1935), Of Mice and Men (1937), Grapes of Wrath (1939), Cannery Row (1945), East of Eden (1952), Sweet Thursday (1954) and Dylan’s own sung novels such as Times They Are a Changin’ and Another Side of Bob Dylan (both1964), Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited (both 1965), Blonde on Blonde (1966) and John Wesley Harding (1967). Apart from the obvious breakthrough achievements of his explosively creative 64-66 period, to me, Harding actually is the quiet masterpiece he thought might makes things smooth like a rhapsody.

It’s also the one that most weirdly echoes Of Mice and Men, especially in one of my favourite songs, “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest”, which has always reminded me Steinbeck’s ballad of Lenny Small and George Milton. I don’t know why, and I don’t need to. “The moral of this story, the moral of this song, is simply that one should never be where one does not belong. So when you see your neighbour carryin’ somethin’, help him with his load. And don’t go mistaking paradise for that home across the road.” And needless to say, Steinbeck’s Cannery Row and Dylan’s Desolation Row are both the same geographical location: our collective unconscious, where were warehouse all of our shared archetypes. Or is that just my imagination? Critics at the time were very testy and complained about Steinbeck’s slightly abstract nature, which to me in retrospect actually really does evoke the impressionistic style of Dylan’s song of the lost ones in his own Row. Even today critics often find Steinbeck difficult to approach in some parts (surprising for so straightforward a writer) as in this somewhat condescending synopsis from Goodreads:

“Cannery Row is a book without much of a plot. Rather it is an attempt to capture the feeling and people of a place, one which is populated by a mix of those down on their luck and those who choose for other reasons not to live “up the hill” in the more respectable areas of town. The flow of the main plot is frequently interrupted by short vignettes that introduce us to various denizens of the Row, most of whom are not directly connected to the story. These vignettes are often characterized by direct or indirect reference to extreme violence: suicides, corpses and the cruelty of the natural world. The “story” of Cannery Row follows the adventures of a group of unemployed yet resourceful men who inhabit a converted fish-shack on the edge of a vacant lot down on the Row.”

All I can say to such unhappy readers of Steinbeck is: “They’re selling postcards of the hanging, they’re painting the passports brown, the beauty parlour is filled with sailors, the circus is in town….and the riot squad they’re restless, they need somewhere to go, as Lady and I look out tonight, from Desolation Row…” As Zollo also accurately opined, “There are few artists in his evolutionary arc whose influence is as profound as Bob Dylan. It’s hard to imagine the art of songwriting without him. There is an unmistakable elegance in Dylan’s words, an almost biblical beauty that has sustained his writing throughout the years.” Naturally I agree, with the one proviso that it isn’t almost biblical, it is biblical, only it’s just a bible first envisioned by the likes of American voices like Thomas Wolfe, Henry Roth and Jack Kerouac, among others. It was those kinds of feral outlanders who first fully utilized the unconscious realms of creative pursuit, not at the expense of conscious or deliberately rational efforts, but in full tandem with them, until the line between conscious and unconscious disappears entirely.

“The best songs to me,” Dylan explains, “my best songs, are songs which are written very quickly. Yeah, very very quickly. Just about as much time as it takes to write it down is about as long as it takes to write it.” That alone is Kerouac writ large, larger even than sad Jack himself could have imagined.

Dylan carefully avoiding the trap of explaining himself to the Nobel Prize audience

And to support that degree of unconscious prowess, Dylan further clarified, “You have to be able to get the thoughts out of your mind. You have to be able to sort them out, if you want to be a songwriter. You must get rid of all that baggage. You ought to be able to sort out all those thoughts, because they don’t mean anything, they’re just pulling you around. It’s important to get rid of those thoughts. Then you can do something with some sort of surveillance of the situation.” Well, that just about explains everything. Some sort of surveillance of the situation. And yet he also warns us that one should be wary of popular entertainers, himself included, or maybe even himself especially, since “It’s not a good idea and it’s bad luck to look for life’s guidance to popular entertainers.” Apparently, when accosted with the famous Van Morrison opinion of his sterling status as the greatest living poet, he demurred, as per usual with this surprising modesty:

“Sometimes. It’s within me. It’s within me to put myself up and be a poet. But it’s a dedication. It’s a big dedication. Poets don’t go to the supermarket. Poets don’t even speak on the telephone. Poets don’t even talk to anybody. Poets do a lot of listening…and usually they know why they’re poets.” This particular poet has even commented on what makes it possible for a single person, someone huge, a titanic figure like Shakespeare for instance, to make such a varied and staggering body of great work, when he observed that “People have a hard time accepting anything that overwhelms them.” A comment that could just as easily help us understand how daunting it is to contemplate Dylan’s own output, let alone his astonishing longevity. “It’s not in anybody’s best interest to think about how they will be perceived tomorrow. It hurts you in the long run.” And this is one lanky and cranky Minnesotan who is definitely in it for the Homeric long run. He forgot long ago that he was even involved in a race at all, since there are so few runners even close to his perpetually nervous footsteps.

His songs, he has declared, are not exactly dreams, as dreamlike as they sometimes may appear, claiming that they’re more of a “responsive nature”. When you need them, they appear, he has said, and he continues to just let them appear, seemingly unaware that this aspect is exactly what makes him so Mozartian in the first place, the apparent lack of conscious effort, to be able to compose music the way most people breathe or drink, but only if first he has felt rejected and decided to write about that rejection from the outside. “Someone who has never been out there can only imagine it really.” Who the hell is this guy? Well, for one thing, apart from being who and what he obviously is, the guy “who would prefer not to”, he’s also the guy who drove so many traditional purists and sticklers for detail almost nuts by winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. People have a long history of complaining about the winner of this prestigious honour, it’s almost a spectator sport, but for a singer of popular lyrical odes to win, that just kind of pushed them all over the edge. But of course, Dylan has already sung about people who didn’t understand what was going on around them, in his Ballad of a Thin Man: “Because something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?”

Ironically, when John Steinbeck won the Nobel in 1962, coincidentally the year Dylan released his first album, people complained about him winning it too, even though he was designated for his “realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humour and keen social perception.” His selection was heavily criticized too and described as “One of America’s biggest mistakes” in one Swedish newspaper. In his acceptance speech in 1962 in Stockholm, Steinbeck said: “The writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man’s proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit, for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love. In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally flags of hope and emulation. I hold that a writer who does not believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.”

The year before, Steinbeck’s last novel, Winter of our Discontent, had examined moral decline in America. It could have been written this year, and it was not a critical success, though some voiced an accurate assessment of “its rightful place as an independent expounder of the truth with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American, both good and bad.” Like Steinbeck’s career, Dylan’s has been long enough, the loneliness of the long distance runner to be exact, to embrace both critical successes, such as the early days and his later years, as well as critical failures, such as his long middle years prior to the end of the century.

Dylan’s own Nobel acceptance speech, as rambling and free flowing as his own personality is, declared in no uncertain and utterly unpretentious terms: “When I first received this Nobel Prize for Literature, I got to wondering exactly how my songs related to literature. I wanted to reflect on it and see what the connection was. I’m going to try and articulate that for you. And most likely it will go in a roundabout way, but I hope what I say will be worthwhile and purposeful. When I first started writing my own songs, the folk lingo was the only vocabulary I knew, and I used it. But I had something else as well. I had principles and sensibilities and an informed view of the world. And I had had that for a while. Learned it all in grammar school. Especially Moby Dick. A way of looking at life, an understanding of human nature and a standard to measure things by. I wanted to write songs unlike anything anybody ever heard.”

That brief excerpt says it all, since he definitely wrote songs no one had ever heard before, and he himself has become a standard to measure things by. Put frankly in fact, the best singer-songwriters are often not the most well adjusted people, naturally enough, and they frequently veer dangerously close to sheer solipsism, the notion that only the self exists or can be proven to exist. But he nonetheless is an exemplar for a truly remarkable creative mystery. And by expressing the utterly subjective aspects of his own experience, he somehow manages to break through to something akin to the purely objective realm, the absolutely interconnected and universally human community of hopes, fears, emotions and obsessions. Dylan songs are like little houses that take out breath away, they are songs which, as a fellow lover of his poetry and music recently told me, we can a live inside of for a while. I liked that observation: songs are houses we can live inside of for a while. They’re also, it seems to me, part of a massive novel that’s he’s still busy writing. I wonder how it ends?