OBJECT LESSONS / Tobacco

“Objects have the longest memories of all. Beneath their stillness, they are alive with all the experiences they have ever witnessed.”

Teju Cole

“Smoking is indispensable if one has nothing to kiss”

Sigmund Freud

By now, everyone everywhere is more than well aware of the difficulties, drawbacks and dangers of tobacco. Unless they’ve been living on Jupiter. But this book is not a polemic for or against anything, far from it in fact, and is rather an exploration of tobacco as a naturally occurring object long before it becomes a product. It is inherently an examination of the social mythology and near magical properties associated with this object from its earliest eras as a ceremonial tool through the varied associations attached to it as a commercial item and style accessory in artistic fictions. The illusory and elusive romance associated with tobacco, and its combusted side effect of iconic swirling smoke, has of course long ago entered our collective cultural bloodstream, largely via novels and movies which have snugly instilled a notion about the behavioral charms of igniting, inhaling, and blowing rings into the immediate social environments we inhabit. Or used to.

Yet still, to this day it’s difficult to imagine a Humphrey Bogart or Clark Gable film without the persistent presence of those white sticks, or even more impactful, Paul Henreid lighting two sticks up and handing one smoldering column back to Bette Davis in the emotional 1942 classic Now Voyager, an intimate offering she always accepts without question; or the literary equivalent of imaginary aloof coolness conveyed by French author Albert Camus in his groundbreaking 1942 novel The Stranger: “I didn’t like having to explain to them, so I just shut up, smoked a cigarette, and looked at the sea.” The taciturn anti-hero stance of his existentially challenged main character is all the more impactful when on imagines his lighting up and engaging in a silent conversation of sorts with the ultimate fire extinguishing equipment in nature in front of him.

As both a film and art critic, author of the recent study of the films of Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett entitled Double Solitaire, and another tome, An Artful Life, on the life and work of Yoko Ono, a controversial artist seldom seen without a burning cigarette clutched lightly during interviews, as well as a literary and popular culture critic who actively writes about the embodied meanings contained in visual art, literature, music and cinema, my intention is solely to unravel the earliest mystical associations connected with this plant, as well as share some appreciation for the sheer archetypal aspects of tobacco as a means of seduction. By far the most salient notion being explored here is that tobacco is itself an embodied meaning representing an even more primal element, that of fire itself, for which tobacco has always been a somewhat easily misunderstood analogue.

It is fire then, in both its quasi-mystical and well grounded practical dimensions, which is the true life force lurking innocently, almost invisibly, behind tobacco. By partaking of what we might as well call its entertainments, tobacco is merely a symbolic stand in for the force we actually want to possess, if only temporarily: fire. The finite duration of its limited life is clearly even more powerfully absorbed into our collective unconscious as a poetic analogy for the brevity of our own bodies on earth. Surely this is why the urge to repeat the ritual of smoking, quite apart from the obvious relationship some of us might have with its psychoactive constituent, i.e. nicotine, is in actuality an urge to once more engage directly with the temporary fire element which commences the ritual per se.

As the great French phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard astutely pointed out: we have only to speak of an object in order to think that we are being objective. “But because we chose it in the first place, the object reveals more about us than we do about it.” One of many paradoxes is that as an author who studies embodied meanings that assume the shape of whatever medium best suits their communicative purpose (i.e. a painting, a building, a novel, a film, an opera etc.) I approach the medium of tobacco with some degree of objectivity, despite Gaston’s admonition: I am not a smoker. I am however a culture critic who, like Bachelard, finds poetic analogies fluently floating around the very existence of any work of art, and as such, I should readily acknowledge that my true interest is in the latent element hidden inside the object known as tobacco, namely, the element of fire.

Another exemplary literary critic with a specialized fondness for the archetypes of poetry, Northrop Frye, has also pointed out the correct methodology necessary to move, for my purposes, from the general to the specific, from supposedly objective studies of the object, to a more fabricated texture available to us not through science by through poetry and art. Frye clarifies for us that science obviously usually begins with a procedure that empirically moves towards a grasp of physical reality which inevitably culminates in the creation of an intellectual construction that explains it, or so we think. A more poetic and artful approach however commences with a different sort of constructive prowess, one which uses the imagination as the means, not to explain but to infer, a notion to be conveyed to others as objects of conception, not necessarily perception. According to Frye, the units of this ability to construct meaning are analogy and identity, which he locates in literature as simile and metaphor. This is a useful strategy to remember as we proceed to explore the supposedly objective nature of an object, such as tobacco, which by its very nature is a referent for potential versus kinetic energies. It also helps us to situate the domain of our interest in what I would term the subject of the object: by unconscious but poetic analogy, the true subject of the object called tobacco is therefore fire.

Whether or not we ignite it as Camus’ character Mersault did, in order to withdraw from social discourse and contemplate his isolation, or use it more ceremonially, as did the original indigenous growers and harvesters of this unique plant, in order to symbolize its spiritually gestative properties, the basic archetypal experience remains a human constant: we want to make love to fire. Thus my short book on the object called tobacco is secretly also about the poetic myths attached to fire, whether or not we strike even a single match. The psychic origins of such basic myths were of course unknown to the fictional characters we read about in novels or watch on the cinema screen. Paul Henreid was not, of course, consciously alluding to the four classical elements when he had Ms. Davis an already burning cigarette he had lodged between his own lips in a symbolic kiss shared with her, and yet the film’s director Irving Rapper was conveying, albeit largely unconsciously, powerful symbol of alchemical transformation which instantly became an intense Hollywood metaphor for the four ancient principles (hot, cold, moist and dry) which birthed the four humours in the organic realm, and in the kinetic inorganic realm, the four elements (of earth, air, fire and water).

These four zones are the key constituents of our imaginative experience, awake or dreaming, whether we know it or not, and they always will be, regardless of how we might adapt their nomenclature to concur more accurately with our current quantum sensibility. Nonetheless it is still best identified with what we can reasonably call the fire-world. Both Frye’s and Bachelard’s contribution to comprehending the magic behind fire (and what I might call the mystic muscle of tobacco) was, as always, a masterful marshalling of what they called poetic metaphors and what I call embodied meanings.

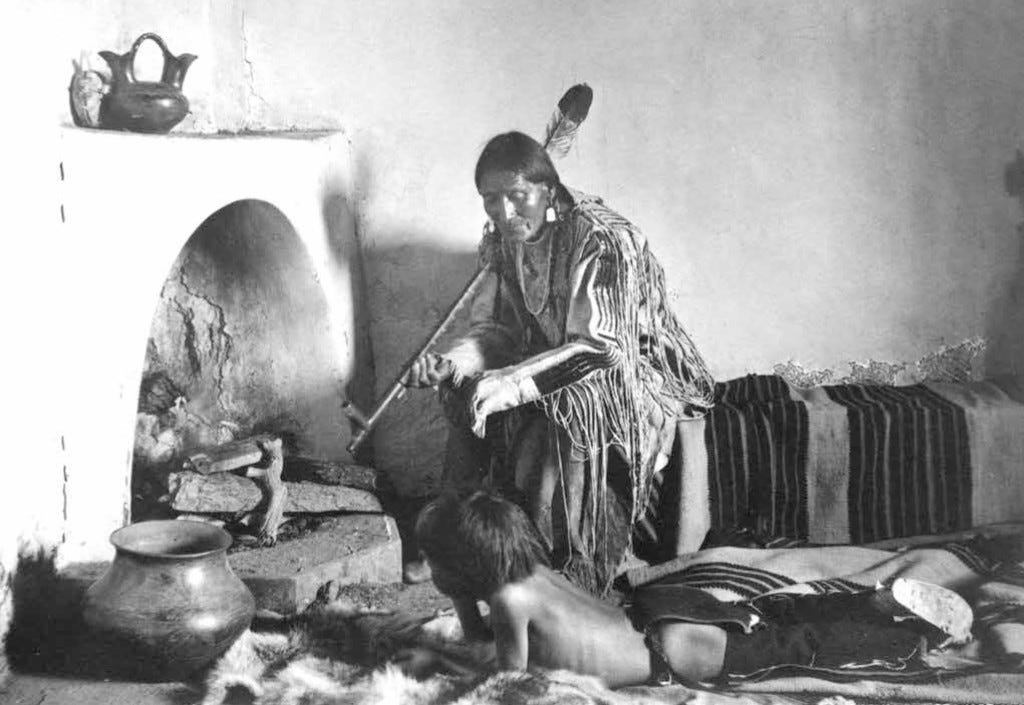

In the ancient origins of our current cultures, this fire-realm was essentially a dance relationship between heaven and earth: the spirit supposedly descends upon us from high above in tongues of fire; the seraphim are apparently angels made of fire, while a human-scale fire was symbolized by the titan Prometheus stealing fire from the gods as a gift to humanity. What did we do with that gift? We lit our cigarettes, cigars and pipes, as if in order to contemplate our newfound status as fire-owners. But long before we lit up, our indigenous ancestors first celebrated that gift in a different manner: by not merely lighting up.

How did those ceremonial procedures celebrate the gift of fire without causing the vessel itself to be mindlessly consumed? That is surely the most informative distinguishing factor at play in the contrast between the ancient and modern history of this seemingly almost metaphysical object: it has been transformed from a resource into a product and finally into a cultural artifact with multiple meanings, all of them embodied within a fascinating series of mythical origins and ironic fates. But most crucially for the purposes of our objective investigative study, the question of whether tobacco is good or bad need never arise at all in these pages. It merely is, and in its smoky mirror are reflected some our most cherished illusions. This brief essay approaches the subject and object in question as if it was a sentient being and explores the consciousness of its subject as a living thing. Which, oddly enough, it actually is. Lessons we can learn by placing tobacco on the analyst’s couch for a therapy session? We might just uncover the lucid dream of a plant which in no way fully deserves the bad reputation it has withstood through its history. The object may be tobacco, but the subject is us.

The most basic facts about tobacco are not mere opinions but rather simply a matter of historical record: the word itself is the commonly used multi-lingual referent for several plants in the genus nicotiana and are part of genus family solanaceae, now generally used for absolutely any of the many products prepared from the their cured leaves. There are seventy five known species of tobacco, with the most common crop being tabacum, which result in dried leaves mainly used (nowadays) for inhaling, but can also be chewed or dipped, or sniffed. Yes, admittedly when inhaled this object does contain a highly addictive substance, the stimulant alkaloid nicotine, as well as harmala alkaloids. This simple fact could of course explain why the formerly widespread availability of it as a recreational drug made it so popular. Accidental pleasures often encourage repetition, despite its risk factors for many life altering ailments affecting the heart, liver and lungs, which explains why in 2008 the World Health Organization (from which America recently withdrew) name tobacco use as the world’s greatest preventable cause of death.

By the time the Euro-visitors arrived, tobacco had already had a huge cultural significance for the indigenous cultures of both Canada and America, centuries before the countries with those names even came into existence. Its traditional uses for trade and ceremony would of course be forever altered by that fateful encounters, as would every other aspect of an ancient and rich heritage. The plant itself had a combination of spiritual medicinal and trading value within a cluster of first nations whose dynamics would shift drastically upon commercial cultivation commencement. It was a plant, often referred to as sacred tobacco, believed to be a direct link to the spirit world and used for shared communication, teaching and expressions of thanks for the gifts given by the land. When it was first introduced to the visitors by native cultures, it brought about a dramatic alteration in social interactions caused by the fusion of the ancient and the new. The arrival of Europeans, and the different value systems they carried with them regarding their own trade items, would become the crucial crux for indigenous and settler relationships. When the fur trade expanded upon the arrival of the visitors, with it also expanded, and altered, the existing traditions around tobacco.

According to Haudenosaunee mythologies, tobacco first grew out of Earth Woman’s head after she died while giving birth to her twin sons, Sapling and Flint. Cultivation sites had existed in Mexico dating as far back as 2000 BCE, and the trading of the item also celebrated the communicative properties believed to associated with its burning embers, the smoke of which carried human thoughts directly to and from the Creator. Europeans, naturally enough, had quite a different perspective regarding both cultivation and commerce. In 1559, Francisco Toledo, a Spanish historian of the so called Indies, was the first European to bring tobacco seeds back to what they ironically called the Old World, following the orders of Spain’s King Philip, and planed the seeds on the outskirts of Toledo. Rapidly, tobacco became so popular that the English colony of Jamestown started using it as currency and commenced exporting the product as a cash crop. Too lucrative to avoid altering the entire landscape of history, including its parallel purposes for contemplation of the metaphysical dimension, it quickly became one of the principal products fueling colonization. Meanwhile the euphoric side effects continued apace, with Swiss doctor Conrad Gesner in 1563 writing that chewing or smoking tobacco leaves gave him “a wonderful power of producing a kind of peaceful drunkenness, while the Spanish doctor Nicholas Monardes wrote a textbooks about herbalism in which he made the unlikely claim that tobacco could cure 36 separate health problems and that “Now we use it to a greater extent for the sake of its virtues than for its beauty.”

Sir Walter Raleigh (about whom John Lennon quipped in his White Album song “I’m So Tired”: “And curse Sir Walter Raleigh, he was such a stupid git.”) brought the first “Virginia” tobacco to Europe in 1578, inspiring another pop song by Tobias Hume called “Tobacco is Like Love”. But it was also denounced, at least by a prescient few, such as the Stuart King James, author of a famous polemic called “Counterblaste to Tobacco”, who declaimed that tobacco use must be denounced, as “a custom loathsome the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black stinking fumes thereof, he nearest thing resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” Who could resist the fumes arising from Hell? Russia, ironically, banned its use entirely except by foreigners, but when Peter the Great ascended the throne (after learning to smoke in England) created a royal monopoly subsequent to revoking all bans, imported over a millions pounds of tobacco per year, and raked in a royal annual profit of almost $30,000 pounds sterling. The stick was lit, the die was cast. Incendiary profit loomed large on the horizon, with the Thirteen American colonies found they could use tobacco as currency to trade with natives and even for paying taxes, fines and license fees. But by far the most drastic consequence of this newly profitable industry was the need for a huge new workforce, which the colonies filled by importing kidnapped Africans to work in its cultivation and harvesting as slave labour. The rest, alas, is our lamentable history.

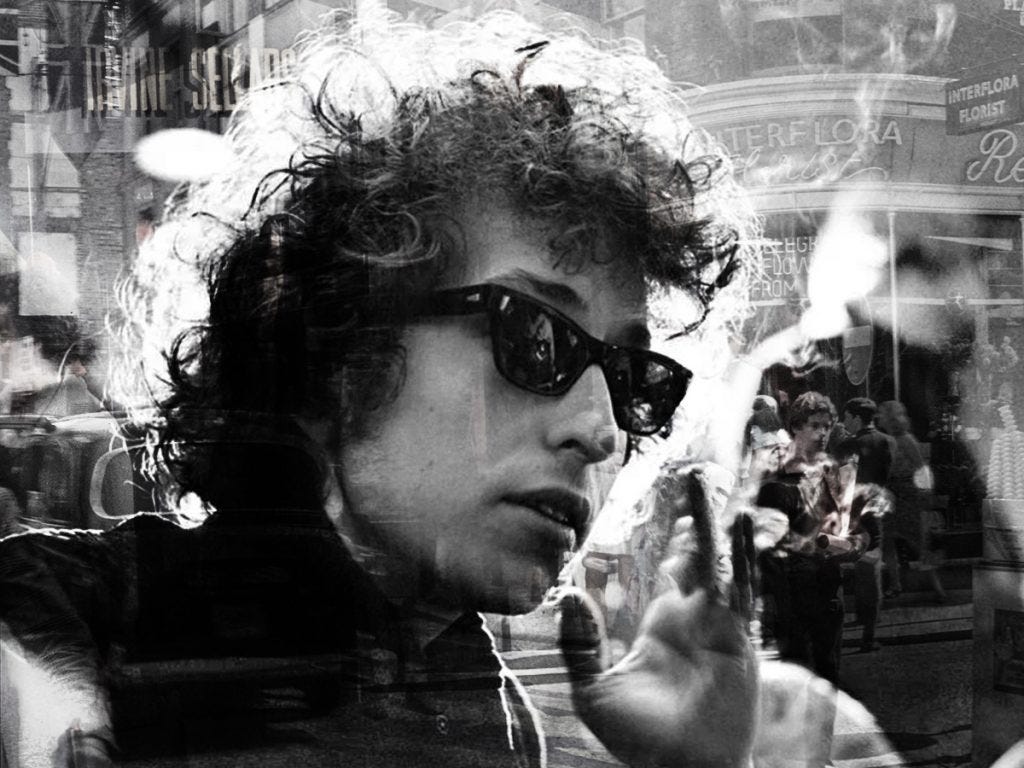

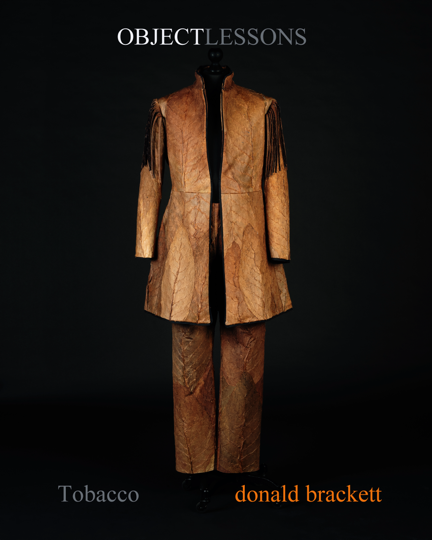

Smoldering money fumes made the world go round, or so both most investors and users thought. These historical details of course may be the most salient reasons for exploring a chronology of the object as if it were a person, which in some ways it actually is, a person who has a childhood, a youth and a senior stage to their mesmerizing passage. This allows us to examine the meteoric ascent of this agricultural artifact in ways which can also embrace its abstract aesthetic properties. Indeed, my wife is a Metis scholar and academic, and her indigenous insights into the living properties of this object have been quite informative in his regard (it is her Metis man’s suit made from tobacco leaves, for instance, which graces this essay’s cover). Tobacco’s objective history however, and the many unconscious cultural associations with it, still remains fascinating for a host of reasons perhaps best comprehended by the psychology of the unknowable. The journey of tobacco, to echo the popular musicians known as the Grateful Dead, has been a long strange trip indeed. So let’s take a closer look into its often arcane biography via its surprising arrivals and departures amongst us. And perhaps the always incisive Bob Dylan said it best, in his caustic tune “Ballad of a Thin Man”: “Because something is happening here, but you don’t really know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?”

Mimi Gellman, Traveler, 2025: Metis men’s suit made of tobacco leaves.

Excellent! What an interesting essay.Yes I smoked at a very young age, (stole them quietly from my mother). I stopped in my 30’s except for a pipe with which I didn’t inhale (ha ha ha) and by my forties I was clean. You also mention Gaston Bachelard, an Author who has fascinated me since I first read (and still do), The Poetics Of Space.