“Language is much closer to film than painting is.”

Sergei Eisenstein, 1929

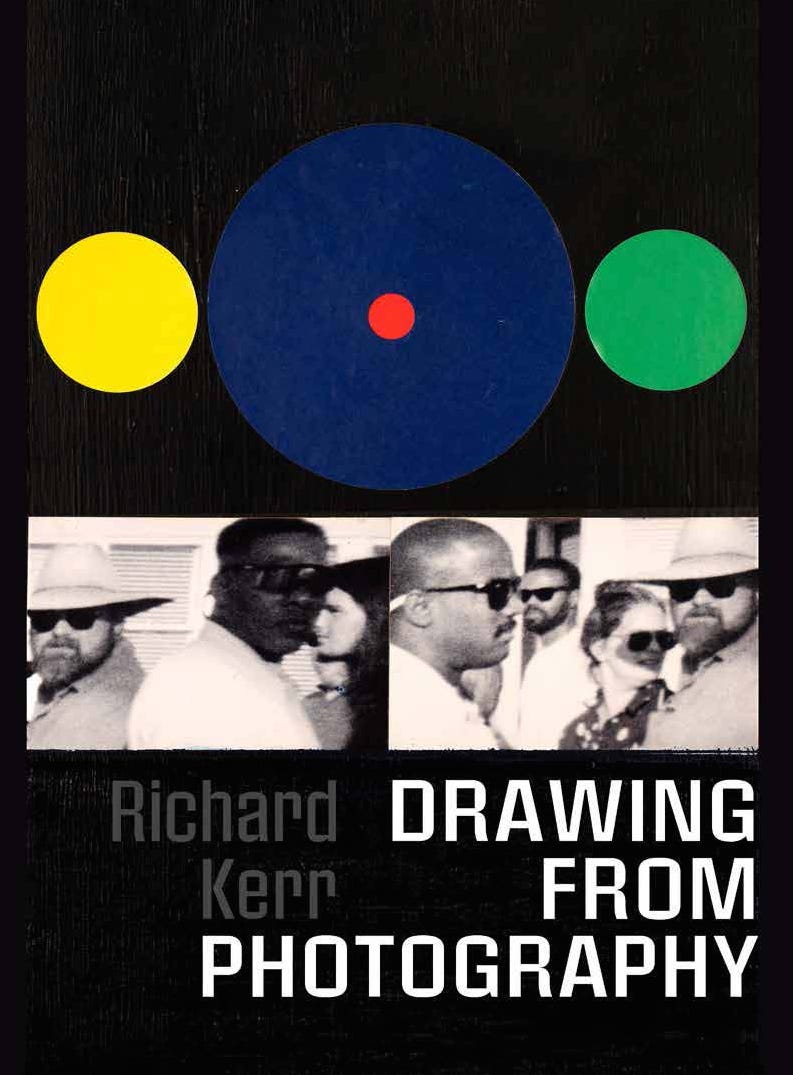

I doubt if I’m jumping to conclusions to say that in all probability both Richard Kerr and I are not huge fans of the digital domain, or even of the 21rst century in general. As an art historian, my judgments on the subject of the most decisive moments in aesthetic evolution, that they all took place from 1840 with the invention of the camera, up to but not including the invention of computers in about 1980, is well known. Yes, admittedly I’m using one to write these words right now, but that’s about as far as it goes. I have long been a proponent of analog forms of art and entertainment, and even bemoan to friends what we have lost from the 20th-century formats and motifs which are receding ever faster in the rear-view mirror as we hurtle full throttle into a future commandeered, and even to some extent HR-managed, by machines with continually more obtuse delivery systems for their so-called content. So much so that we can often lose sight of the fact that the actual aesthetic content, which is most often an expression of human longing or regret, hasn’t really changed that much over many generations or iterative systems of delivery, and that only the platter on which the sensory information is being served has altered.

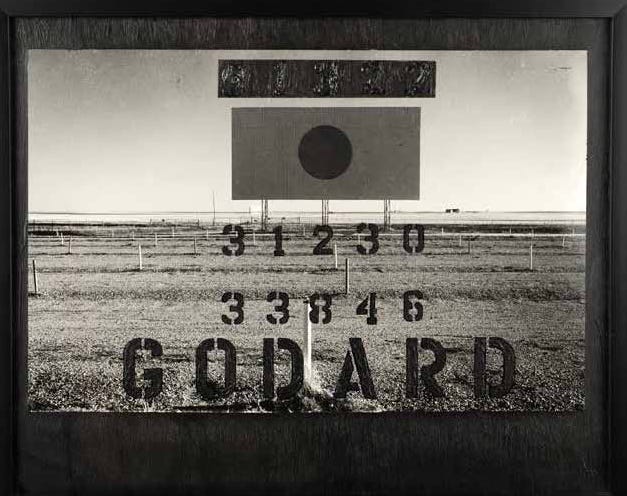

Godard, Saskatchewan, 1986

I suspect, I even hazard to say we suspect, that the human appetite for images will still be being transmuted into the 22nd century, although probably mashed into a new style format engineered by some audacious new vehicle or other. This is a nostalgic dilemma I often embrace, and I concur with MIT’s author Robert Hassan, whose affections for the analog mode of expressing the human allegory feel reassuringly familiar. In his book Analog, he asks us to consider a salient question: “Why, surrounded by screens and smart devices, do we still feel a deep connection to the analog form, to books, vinyl records, fountain pens, Kodak film, and other non-digital tools?” David Sax, author of The Future is Analog, went even further when he observed, “The digital future, we’re assured, is only a matter of time. But we become lost when we try to replace the human with the digital. The full-body roller coaster that is human existence on planet earth: when we try to replace that reality with a digital facsimile, we are lost. The future is analog, because we ourselves are analog.” That, it strikes me, is also one of the pivotal messages conveyed by the art of Richard Kerr. Or so it seems to me.

Is It / LA, 1990

Having had the pleasure of writing a commentary on Kerr’s first book Inventory: The Motion Picture Weaving Project, I am now even more pleased to approach the impressive nearly career-long multi-media retrospective of his ongoing dedication to images and their emotive power in our lives. In my earlier observations, Frozen Music: The Celluloid Dreams of Richard Kerr, I focused our attention on the body of work which forms the last section in this new book, and I was especially taken by the final piece, one he called “Indeterminacy”, in his new book. It’s a term that elegantly encapsulates the fuel I feel behind his overall working method, one that hinges on uncertainty and the necessity for viewers to make their own decisions about the work’s meaning. In music it also implies a composer’s intention that certain aspects of an experience are left open to what John Cage called chance operations, and to the interpreter’s free choice. This is the inherent value of Kerr’s emphasis on ‘less meaning, more being’: we the viewers help to construct the tale he tells us.

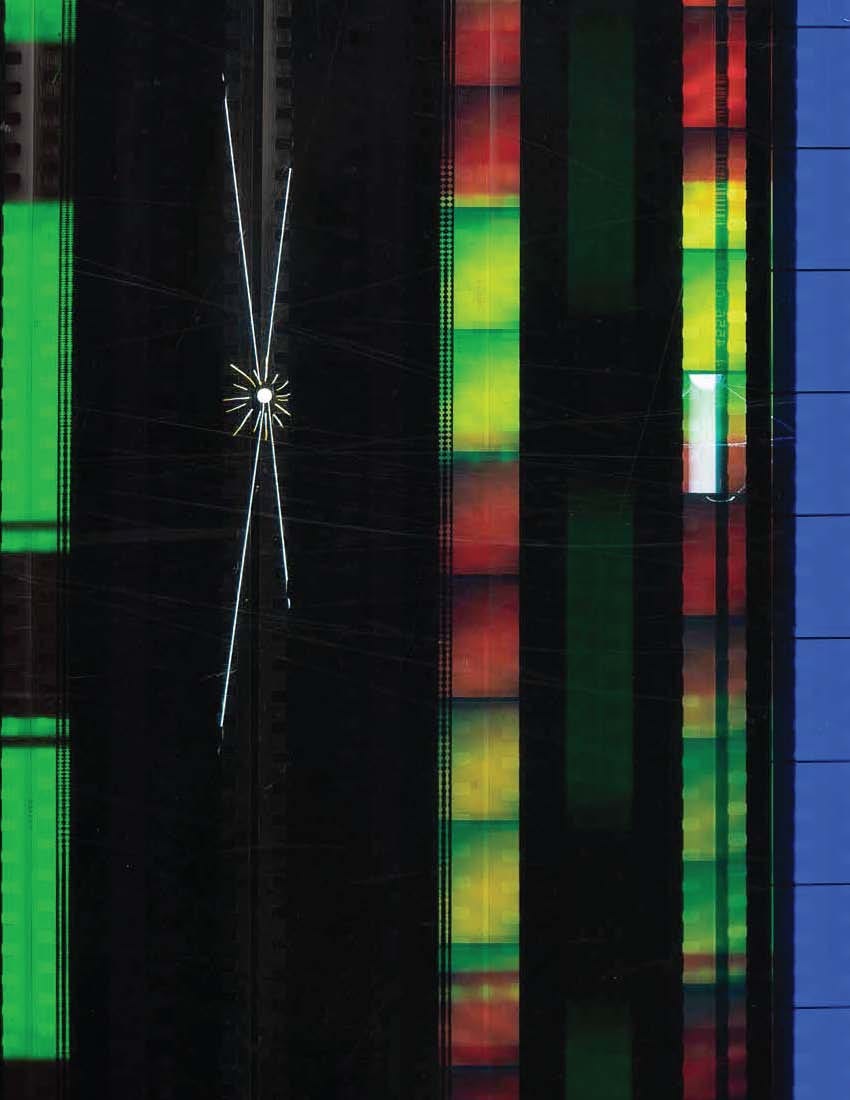

Motion Picture Weaving Project

My earlier assessment asserted that by making sculptural objects from collaged strips of 35 mm films he was freezing the music of montage in order to allow his keen eye to properly gauge the aesthetics of the dream state that cinema induces. In this current carefully assembled selection of sophisticated mixed media works, alluringly titled Drawing From Photographs, Kerr has taken us even deeper into the almost atavistic realm of images. His presentation also has the feeling of a curated exhibition culled from the long term domain of his personal commitment to a dynamic forward flow that he identifies by the astute creative formula: look, make, learn, teach. In these works he calibrates the poetics of stillness, another kind of induced dream altogether: a motionless reverie, or daydream. But the immediately discernible fabula he unleashes is still blissfully laden with a certain rhythmic structure, an almost narrative but stationary montage that tells a story through deft juxtaposition. And we listen with our eyes alone.

Field Trip, Saskatchewan, 1990

Kerr’s new publication convinces me even more that there is a cogent force of visual music behind his work. Cadence is the beat, time and measure of rhythmic motion, and in this case the regular rise and fall of visual soundwaves. From the moment I opened the first section in the book’s sequence, “Field Trip, 1988-1992”, I felt I was following the forward motion of a story told in diptych forms, with each pair adding to the previous and proceeding one, while also being engaged in an almost but not quite entirely aleatory balance in the two-page spreads that harken back to the call and response mode in blues and gospel music. Meanwhile cascade, another intriguing term that sprang to mind as I was traversing his river of images, has a double meaning which can further illuminate Kerr’s gentle brand of visual alchemy. It references, first, anything that resembles a waterfall, especially in seeming to flow in abundance. And secondly, even more arcane, cascade is a way to maximize the resource efficiency through a double use of raw materials, specifically of material use in the first step and energy use in the second.

Washington DC, 1992

To clarify this slightly obscure terminology somewhat: his first key raw material is his source photographs, whether his own or otherwise found, thus ‘drawing from photographs’. His second maximal utility is his harnessing of the energy content that comes to life via montage, repetition, sequence, and every other kind of visual irony he employs to explore any given subject matter and theme. “Arizona Drive By, 1992” and “Flag Study, 2002” have a similar road trip journal kind of feeling that also builds through the architecture of assemblage and movement. All three of these sections resonate, in the most powerfully creative way, with the historical works of Robert Frank, Larry Fink, Joel Meyerowitz, Elliott Erwitt and to some extent, Garry Winogrand. With quite a few important provisos. Being well aware of how distasteful it is for artists to feel that they’re are being compared to each other, I hasten to point out that this is, far from comparative, merely the recognition of an important shared spiritual frequency or vibrational wavelength.

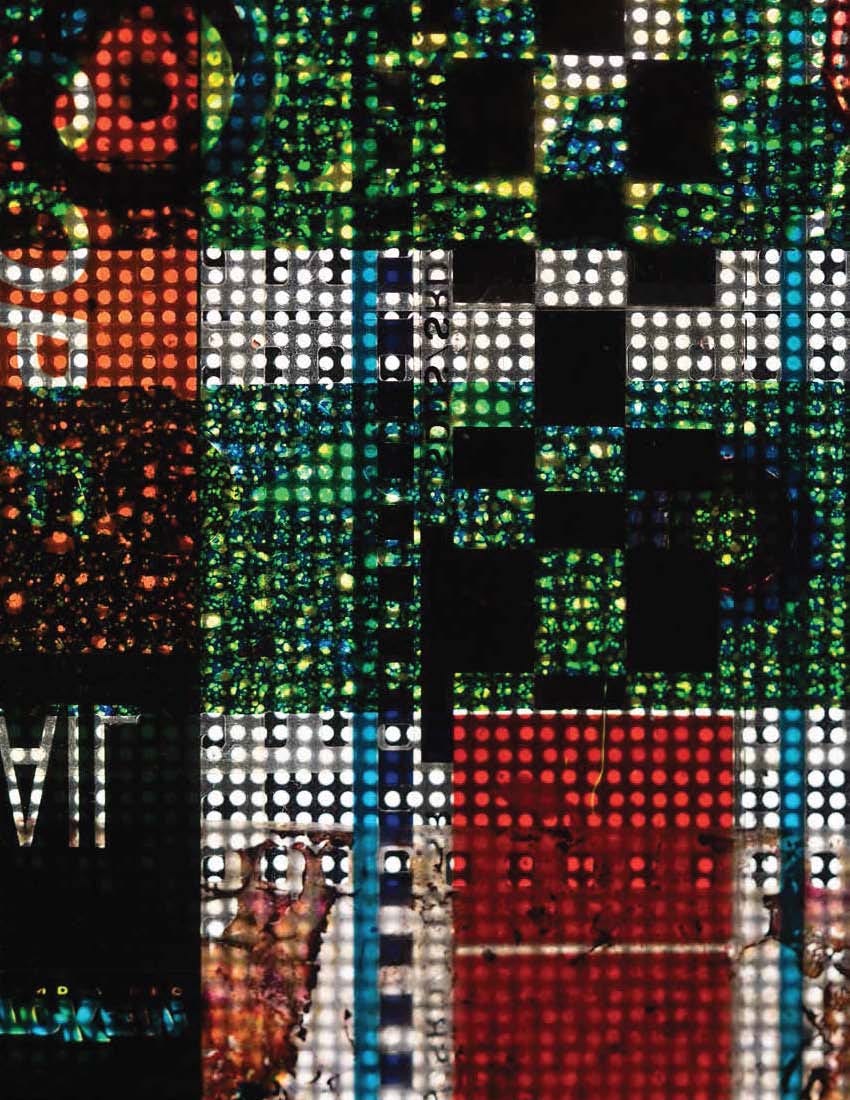

This is where the cadence and cascade elements come strongly to the forefront. “Demi Monde, 2003” has herein been ably explicated by Stephen Broomer in a manner requiring no more additives from me. His take is a superlative exploration of Kerr’s working methods and aesthetic mode of operations, and in assessment is practically a primer on the politics of the Kerr image-making machine and the democracy of its shared feeding frenzy. This leaves me free to concentrate on those other salient ingredients in Kerr’s oeuvre (we definitely both enjoy surrendering to our image-fetish with a celebratory abandon) by noting that my favourite thematic sections in the book, “Wholly Holy, 2017”, “Work With Paint, 2017-2024” and “Photography With Text, 1982-2023” each lands a beautiful blow to the chin of what French semiotician Roland Barthes once called the “empire of signs”: interpreting the meaning-making structures of signification.

A sign, we should remember, is anything that communicates intentional or unintentional meanings and feelings to the sign’s interpreter. Also to be remembered: often the greatest meanings are those precious unintentional ones. Indeed, as Sax emphasizes, a digital artistic encounter is not quite the same as a real haptic experience of a physical object, no matter how fanciful it might become. As Sax put it so succinctly: “Humans have genuine social needs and if those needs aren’t met, we will actually perish. For the past few years we have overdosed on digital. Now, we’re reckoning with an epic hangover. We face a choice, strap on our headsets, double down, and plunge deeper into the metaverse. Or step back, reconnect to our bodies and the world and find a way to build a more human future.” It is abundantly clear how we got to where we are and why we need to actively appreciate more cogently what the analog domain really was, and still is, rather than pompously imagining it as something antique to be left behind. Kerr demonstrates to us how the past is prologue.

Something also inherently touch-oriented in Kerr’s works reminds us that we ourselves are still analog, despite the latest technics and tools we’ve devised or inherited, and diversely conceived and executed art such as his is almost mnemonic in nature, being parallel to our heightened senses. Thus they relate to and use signals represented by a continuously changing physical quality such as spatial position within a highly variable analog process, one based on haptic sensations of continuity and flow. “In Alphabetical Order, 2012”, with its verging on pop presentation, and “3:2 Aspect Ratio, 2024” with its multiple repurposing of the mount format, celebrate the quotidian perspective of near and far, far and wide. Kerr’s work, as demonstrated via the thematic sections he has chosen for his book, travels far and wide in a splendid tapestry of shivery smiles woven from the nature of several overlapping things: memory, wonderment and enchantment.

Ultimately, the pieces illustrated in this book are embodied meanings: they are symbols only of themselves. Drawing From Photographs is also a kind of living archive of sorts, collecting nearly four decades of one artist’s reflections on what it means to look at looking, to think by making, and to learn through teaching. My personal favourite among his elegant sign-processes might be Kerr’s “IMAX Sculpture, 2020”, from the “Photography to Collage, 1997-2024” section, which with its hand-treated acrylic-frames, magnetics and fragments of Imax 65 mm film strips operating in a variable scale and site format, is a modular montage sculpture perhaps closest to his stylistically parallel “Motion Picture Weaving Project.” For me, this piece is a veritable altar for the secular worship of images, rendering them as truly 21rst Century sacred icons.

IMAX Sculpture, 2020

I hope this piece is somehow preserved and spared any potential upcoming apocalyptic event, so that future civilizations engaged in archaeological digs might unearth it an attempt to submit it to the sort of interpretive decoding exercises that the Rosetta Stone underwent. Better yet, I wish it, among a few other Kerr works, had been placed in Voyager I and sent spinning off to the edges of our vast galaxy, to be discovered by a species of being for whom we are the aliens, not them. I’d like them to be able to contemplate for themselves our great and primitive passion for images. Since that vessel is now some fifteen billion miles away and still traveling, I’ll simply have to savor this notion as a private reverie I suppose. But it’s still a tasty one. And so is this book.

“In painting the form arises from abstract elements of line and colour, while in cinema the material concreteness of the image as an element within the frame presents the greatest difficulty in manipulation. This is the meaning of montage.”

Sergei Eisenstein, 1945

(Note: Drawing From Photographs is a limited edition art book and is available directly from the artist. For enquiries: richard.kerr@concordia.ca )